I’ve just returned from a weekend at the border in the southern Arizona desert where I participated in a delegation of 60 faith leaders from around the country in an initiative called “Faith Floods the Desert,” supporting the movement No More Deaths/No Mas Muertes (NMD). It was a powerful and at times overwhelming experience. I’ll try to do my best to do it justice here.

As I mentioned in my previous post, No More Deaths is an organization that provides humanitarian relief to migrants, mobilizes search and rescue operations for disappeared migrants, and documents how border enforcement pushes migration into some of the most remote and dangerous areas in Arizona’s deserts. “Faith Floods the Desert” was an initiative sponsored jointly between NMD, the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee, and the Unitarian Universalist Association in response to the increasing criminalization of migrant relief work by the U.S. government.

Earlier this year Scott Warren, a humanitarian aid provider with NMD, and two people receiving humanitarian aid were arrested by U.S. Border Patrol. Now Warren is facing a federal felony charge, and eight other NMD volunteers have been charged with federal misdemeanor charges relating to their humanitarian aid work on the Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge, a vast and remote stretch of land that shares 56 miles with the U.S.-Mexico border. (Warren’s arrest is particularly suspicious as it occurred eight hours after NMD released a video of border police dumping water and destroying supplies left by relief workers.)

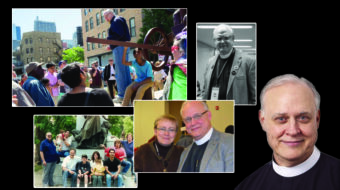

Our delegation gathered last Saturday in Ajo, Ariz., a small former copper mining town located 40 miles north of the U.S./Mexico border. While the majority of clergy were UU ministers, I was honored to be a part of a five-person rabbinical cohort (with my colleagues Rabbis Margaret Holub, Ari Lev Fonari, Shahar Colt and Salem Pearce). On our first full day, we attended a briefing with leaders and volunteers from NMD, who explained the history and context of the crisis at the border.

For those interested in learning more, I strongly recommend their report, “Disappeared: How the US Border Enforcement is Fueling a Missing Persons Crisis.” Among other things, the report does a thorough job of describing how the U.S. Border Patrol adopted an enforcement strategy called “Prevention Through Deterrence” in 1994—the same year that the U.S. signed the NAFTA treaty. As the report notes:

“With the implementation of this policy, the Border Patrol sought to control the Southwest border by heightening the risks associated with unauthorized entry. To do so, the agency concentrated enforcement and infrastructure to reroute migration away from urban ports of entry and into wilderness areas. By pushing traffic into remote and hostile terrain, the agency speculated that border crossers would now find themselves ‘in mortal danger’ when attempting to enter the US without authorization. The increased danger was intended to then deter other people from considering the journey, with the overall goal of preventing migration….

“As a consequence of Prevention Through Deterrence, thousands of people have perished in the borderlands due to dehydration, heat-related illness, exposure, and other preventable environmental causes. Extreme heat and bitter cold, scarce and polluted water sources, treacherous topography, and near-total isolation from possible rescue are used as weapons of border enforcement.”

In other words, the U.S. government is responsible for the policy that is knowingly causing the migration of immigrants into “remote and hostile terrain”—as well as the policy that sends the border patrol to literally hunt them down. And now our government is actually arresting those who are trying to keep them alive.

On Saturday evening, our delegation gathered in the Ajo town plaza for a press conference. I was particularly moved by the remarks of Reverend Susan Frederick-Gray, President of the Unitarian Universalist Association:

“We need to recognize that this system of criminalization and cruelty is devastating the lives of children and parents and families here at the border, all over the world, and also in the interior of the United States. These same mechanisms of criminalization are aimed not just at migrants and activists, but they are aimed at the poor, they are aimed at communities of color, they are aimed at people with mental health issues. Everywhere, criminalization is undermining human rights and civil rights here in the United States. Those of us who identify as Americans, we lose some of our humanity when we allow this to continue.”

In my remarks, I made a similar point, connecting the criminalization of relief work at the border with the very same phenomenon in Gaza and Palestine:

“I can’t help but be mindful of the fact that just last week there was a boat that was taking humanitarian goods to Gaza that was intercepted by the Israeli navy. The volunteer workers on board were brutalized, incarcerated and ultimately deported. This is the same work that we are doing, ultimately, and I think it’s very important for all of us to understand that what’s going on here at the border is going on in Gaza and too many places around the world. As we stand in solidarity here, we need to be mindful that we are standing in solidarity in so many other ways as well.”

On Sunday morning, our delegation was split into two groups. One went south to distribute water via the Devil’s Highway, a well-known and infamous road extending through some of the most remote and desolate regions of the Sonoran Desert. Our group traveled to the Charlie Bell Road, a trail in the Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge along the Growler Mountain Range. Both of these are among the few entrances to West Desert that are open to the public.

Our group of 20 consisted of faith leaders, media, and NMD medics and EMTs, and we traveled into Charlie Bell in four trucks. Because our action was well publicized beforehand, we fully expected to encounter law enforcement, and as it turned out, several officers from the Department of Fish and Wildlife stopped us at the entrance to see our entrance permits. They also asked to see the ID’s of everyone who was in the lead car. Although it was not entirely a surprise, volunteers from NMD told us this was the first time any of them had been stopped by the “Fish Cops” at the entrance to the refuge.

The day quickly became blisteringly hot—by noon it was already 110 degrees. We walked carrying two to three gallons of water each approximately one and a half miles down the trail along the mountain range. When we arrived at a well marked with a beacon and flag, we wrote messages of hope and solidarity on our plastic jugs of water and set them down. Afterwards, several of us distributed additional bottles at another site close by.

This well, by the way, is not intended for use by human beings: It was constructed by the nature preserve to water a nearby trough for wildlife. As we peered inside, we could see that the water inside was dirty and mossy, clearly unfit for human consumption. The irony did not need to be pointed out to any of us: Those who maintain this area provide water for animals, while the water others leave for human beings is confiscated and destroyed.

We also saw clear signs in the vicinity that migrants had passed through. Among them: slippers made out of carpet worn over shoes to hide their tracks and a wrapper of electrolyte powder purchased in Mexico. The evidence of the presence of migrants was not hard to find and it all seemed fairly familiar to our NMD guides.

All in all, we spent the better part of the morning and afternoon in the open desert, traveling on foot approximately 3.5 miles. The final 1/2 mile was uphill, and though I made a point of hydrating constantly, the heat was constant and overpowering. (It was so hot, in fact, that the glue on the bottom of my shoes literally melted the soles off of my feet.) I cannot begin to comprehend how migrants to walk 80 to 100 miles through such extreme terrain and hostile conditions. I cannot consider it anything but a sacrilege that our government knowingly drives human beings into a region such as this under the guise of “deterrence.”

In the evening, we attended a monthly memorial vigil in the Ajo town plaza for migrants who perished in the West Desert region. The majority of names spoken aloud were “Desconocido” (“Unknown”). According to NMD, at least 128 bodies were recovered just last year, including 57 in the desert where we focused our action. Many of them will never be identified. And many more will continue to remain undiscovered in the wilderness in areas that are inaccessible to relief workers.

At the end of our stay, my colleague Rabbi Ari Lev Fonari wrote the following on his Facebook page:

“What I know to be true:

“1. Water is life.

“2. Migration is an organic part of life, a human right and a tactic of survival.

“3. The border is an unnatural divide generating industry and environmental harm.

“4. People have been crossing dangerous deserts by the light of the moon seeking safety and freedom, hunted by the state and sustained by their faith, for as long as human beings have been alive.”

Ari Lev speaks my head and my heart. I’ve visited several militarized borders now—and I am more convinced than ever that they serve no other purpose than to shore up the power and profit of those who design, construct and maintain them. Now more than ever we must fight for a world without borders, for a world where freedom of movement over our shared earth is respected and honored.

In the meantime, however, we must reckon with the world as it currently is: a world in which nations hunt down those who dare to cross these unnatural lines in search of a better life for themselves and their families. A world in which governments criminalize those who seek to offer them life-saving relief and assistance. A world in which the powerful assume no one will ultimately care about the humanity they deem to be disposable.

In the end, it will be up to all of us to prove them wrong.

I’m deeply grateful to those in the UUA and UUSC for convening this delegation, the volunteers of No More Deaths/No Más Muertes, whose work taught us simple but powerful lessons about the discipline of human decency, and the wonderful people of Ajo who opened their community and their homes to us.

Please support the work of No More Deaths by signing this letter to the land managers of the West Desert, demanding that they “acknowledge the gravity and severity of the humanitarian crisis occurring on the lands (they) steward, and take immediate action to protect the lives and dignity of all people on these lands by upholding the right to receive and provide humanitarian aid.”

All photos taken by Rabbi Brant Rosen.

Reposted by permission of the author. The original posting on Rabbi Rosen’s blog Shalom Rav can be found here.

Comments