Good School, Rich School; Bad School, Poor School

The inequality at the heart of America’s education system

HARTFORD, Conn.—This is one of the wealthiest states in the union. But thousands of children here attend schools that are among the worst in the country. While students in higher-income towns such as Greenwich and Darien have easy access to guidance counselors, school psychologists, personal laptops, and up-to-date textbooks, those in high-poverty areas like Bridgeport and New Britain don’t. Such districts tend to have more students in need of extra help, and yet they have fewer guidance counselors, tutors, and psychologists; lower-paid teachers; more dilapidated facilities; and bigger class sizes than wealthier districts, according to an ongoing lawsuit. Greenwich spends $6,000 more per pupil per year than Bridgeport does, according to the State Department of Education.

The discrepancies occur largely because public school districts in Connecticut, and in much of America, are run by local cities and towns and are funded by local property taxes. High-poverty areas such as Bridgeport and New Britain have lower home values and collect less taxes, and so can’t raise as much money as a place like Darien or Greenwich, where homes are worth millions of dollars. Plaintiffs in a decade-old lawsuit in Connecticut, which heard closing arguments earlier this month, argue that the state should be required to ameliorate these discrepancies. Filed by a coalition of parents, students, teachers, unions, and other residents in 2005, the lawsuit, Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding (CCJEF) v. Rell, will decide whether inequality in school funding violates the state’s constitution.

“The system is unconstitutional,” the attorney for the plaintiffs Joseph P. Moodhe argued in Hartford Superior Court earlier this month, “because it is inadequately funded and because it is inequitably distributed.”

Connecticut is not the first state to wrestle with the conundrum caused by relying heavily on local property taxes to fund schools; since the 1970s, nearly every state has had litigation over equitable education, according to Michael Rebell, the executive director of the Campaign for Educational Equity at Teachers College at Columbia University. Indeed, the CCJEF lawsuit, first filed in 2005, is the state’s second major lawsuit on equity. The first, in 1977, resulted in the state being required to redistribute some funds among districts, though the plaintiffs in the CCJEF case argue the state has abandoned that system, called Educational Cost Sharing.

In every state, though, inequity between wealthier and poorer districts continues to exist. That’s often because education is paid for with the amount of money available in a district, which doesn’t necessarily equal the amount of money required to adequately teach students.

“Our system does not distribute opportunity equitably,” a landmark 2013 report from a group convened by the former Education Secretary Arne Duncan, the Equity and Excellence Commission, reported.

This is mainly because school funding is so local. The federal government chips in about 8 to 9 percent of school budgets nationally, but much of this is through programs such as Head Start and free and reduced-price lunch programs. States and local governments split the rest, though the method varies depending on the state.

Nationally, high-poverty districts spend 15.6 percent less per student than low-poverty districts do, according to U.S. Department of Education. Lower spending can irreparably damage a child’s future, especially for kids from poor families. A 20 percent increase in per-pupil spending a year for poor children can lead to an additional year of completed education, 25 percent higher earnings, and a 20-percentage-point reduction in the incidence of poverty in adulthood, according to a paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Violet Jimenez Sims, a Connecticut teacher, saw the differences between rich and poor school districts firsthand. Sims, who was raised in New Britain, one of the poorer areas of the state, taught there until the district shut down its bilingual education programs, at which point she got a job in Manchester, a more affluent suburb. In Manchester, students had individual Chromebook laptops, and Sims had up-to-date equipment, like projectors and digital whiteboards. In New Britain, students didn’t get individual computers, and there weren’t the guidance counselors or teacher’s helpers that there were in Manchester.

“I noticed huge differences, and I ended up leaving because of the impact of those things,” she told me. “Without money, there’s just a domino effect.” Students frequently had substitutes because so many teachers got frustrated and left; they didn’t have as much time to spend on computer projects because they had to share computers; and they were suspended more frequently in the poor district, she said. In the wealthier area, teachers and guidance counselors would have time to work with misbehaving students rather than expelling them right away.

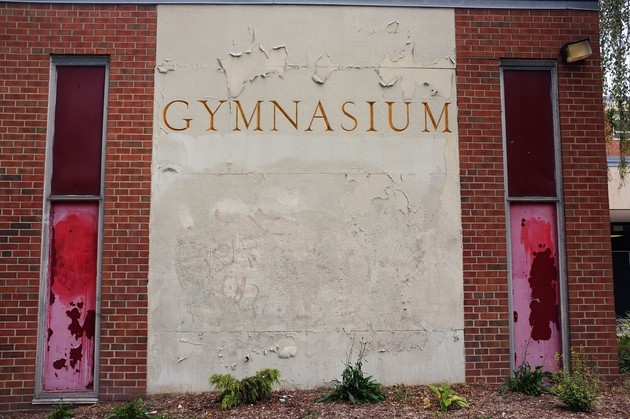

Testimony during the CCJEF trial bears out the differences between poor areas like New Britain, Danbury, Bridgeport, and East Hartford, and wealthier areas like New Canaan, Greenwich, and Darien. Electives, field trips, arts classes, and gifted-and-talented programs available in wealthier districts have been cut in poorer ones. New Britain, where 80 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, receives half as much funding per special-education student as Darien. In Bridgeport, where class sizes hover near the contractual maximum of 29, students use 15-to 20-year-old textbooks; in New London, high-school teachers must duct tape windows shut to keep out the wind and snow and station trash cans in the hallways to collect rain. Where Greenwich’s elementary school library budget is $12,500 per year (not including staffing), East Hartford’s is zero.

All of this contributes to lower rates of success for poorer students. Connecticut recently implemented a system called NextGen to measure English and math skills and college and career readiness. Bridgeport’s average was 59.3 percent and New Britain 59.7 percent; Greenwich, by contrast, scored 89.3 percent and Darien scored 93.1. Graduation rates are lower in the poorer districts; there’s more chronic absenteeism.

The crux of the state’s case is that it spends enough on education, and that Connecticut has one of the country’s best public-school systems. The Educational Cost Sharing formula gets tinkered with by the legislature, the state says, and Connecticut still spends more on poor districts than many regions of the country. It says that what CCJEF is asking is essentially $2 billion more in taxpayer funding to make schools equitable—a sum that would be difficult to raise in a cash-strapped state.

“While we wholeheartedly share the goal of improving educational opportunities and outcomes for all Connecticut children, it is the state’s position both that we are fulfilling our constitutional responsibilities and that the decisions on how to advance those goals are best left to the appropriate policymakers: local communities and members of the General Assembly,” Jaclyn M. Falkowski, a spokeswoman for Connecticut Attorney General George Jepsen, told me in an email.

Yet the fact remains that delegating education funding to local communities increases inequality. That’s especially true in Connecticut, which has some of the biggest wealth disparities in the country. Indeed, in Connecticut, rich and poor districts often abut each other. Bridgeport is in the same county as Greenwich and Darien; East Hartford is poor, but nearby West Hartford is affluent. How did a state like Connecticut, which had one of the first laws making public education mandatory, become so divided? And why does such an unequal system exist in a country that puts such a high priority on equality?

Many of the problems that have arisen in Connecticut’s school system can be traced back to how public education was founded in this country, and how it was structured. It was a system that, at its outset, was very innovative and forward-thinking. But that doesn’t mean it is working for students today.

“The origins were very progressive, but what might have been progressive in one era can become inequitable in another,” Rebell told me.

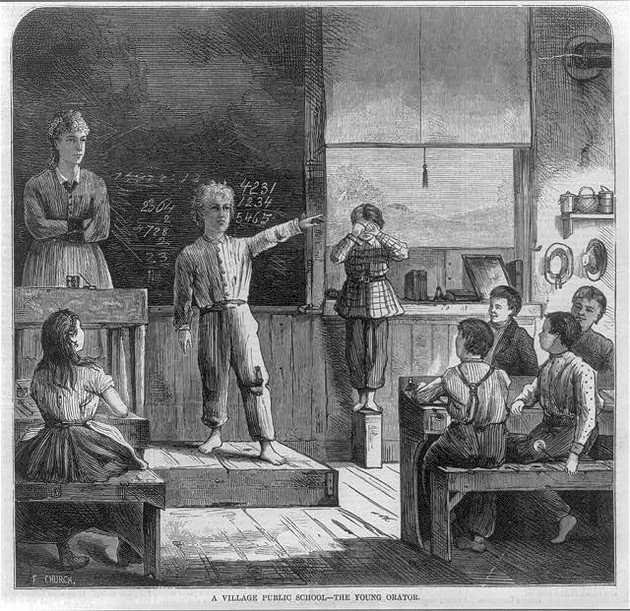

In the early days of the American colonies, the type of education a child received depended on whether the child was a he or a she (boys were much more likely to get educated at all), what color his or her skin was, where he or she lived, how much money his or her family had, and what church he or she belonged to. States like New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York depended on religious groups to educate children, while southern states depended on plantation owners, according to Charles Glenn, a professor of educational leadership at Boston University.

It was the Puritans of Massachusetts who first pioneered public schools, and who decided to use property-tax receipts to pay for them. The Massachusetts Act of 1642 required that parents see to it that their children knew how to read and write; when that law was roundly ignored, the colony passed the Massachusetts School Law of 1647, which required every town with 50 households or more hire someone to teach the children to read and write. This public education was made possible by a property-tax law passed the previous year, according to a paper, “The Local Property Tax for Public Schools: Some Historical Perspectives,” by Billy D. Walker, a Texas educator and historian. Determined to carry out their vision for common school, the Puritans instituted a property tax on an annual basis—previously, it had been used to raise money only when needed. The tax charged specific people based on “visible” property including their homes as well as their sheep, cows, and pigs. Connecticut followed in 1650 with a law requiring towns to teach local children, and used the same type of financing.

Property tax was not a new idea; it came from a feudal system set up by William the Conquerer in the 11th century when he divided up England among his lieutenants, who required the people on the land to pay a fee in order to live there. What was new about the colonial property-tax system was how local it was. Every year, town councils would meet and discuss property taxes, how much various people should pay, and how that money was to be spent. The tax was relatively easy to assess because it was much simpler to see how much property a person owned that it was to see how much money he made. Unsurprisingly, the amounts various residents had to pay were controversial. (A John Adams–instituted national property tax in 1797 was widely hated and then repealed.)

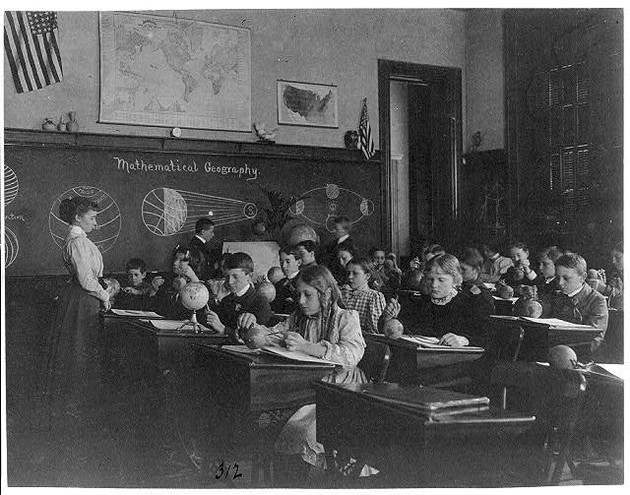

Initially, this system of using property taxes to pay for local schools did not lead to much inequality. That’s in part because the colonies were one of the most egalitarian places on the planet—for white people, at least. Public education began to become more common in the mid-19th century. As immigrants poured into the country’s cities, advocates puzzled over how to assimilate them. Their answer: public schools. The education reformer Horace Mann, for example, who became the secretary of the newly formed Massachusetts Board of Education in 1837, believed that public schooling was necessary for the creation of a national identity. He called education “the great equalizer of the conditions of men.”

Though schooling had, until then, been left up to local municipalities, states began to step in. After Mann created the Board of Education in 1837, he lobbied for and won a doubling of state expenditures on education. In 1852, Massachusetts passed the first law requiring parents to send their children to a public school for at least 12 weeks.

The idea of making free education a right was controversial—the “most explosive political issue in the 19th century, except for abolition,” Rebell said. Eventually, though, when reformers won, they pushed to get a right for all children to public schooling into states’ constitutions. The language of these education clauses varies; Connecticut’s constitution, for example, says merely that “there shall always be free public elementary and secondary schools in the state,” while Illinois’ constitution requires an “efficient system of high-quality public educational institutions and services.”

Despite widespread acceptance of mandatory public education by the end of the 19th century, the task of educating students remained a matter for individual states, not the nation as a whole. And states still left much of the funding of schools up to cities and towns, which relied on property tax. In 1890, property taxes accounted for 67.9 percent of public-education revenues in the U.S. This means that as America urbanized and industrialized and experienced more regional inequality, so, too, did the schools. Areas that had poorer families or less valuable land had less money for schools.

In the early part of the 20th century, states tried to step in and provide grants to districts so that school funding was equitable, according to Allan Odden, an expert in school finance who is a professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. But then wealthier districts would spend even more, buoyed by increasing property values, and the state subsidies wouldn’t go as far as they once had to make education equitable.

The disparities became more and more stark in the decades after World War II, when white families moved out of the cities into the suburbs and entered school systems there, and black families were stuck in the cities, where property values plummeted and schools lacked basic resources. In some states, where school districts were run on the county level, costs could be shared between rich and poor districts by combining and integrating them, especially after Brown v. Board of Education. But in states like Connecticut, with deeper histories of public schooling, there were hundreds of separate districts, and it was much more difficult to combine them or to equalize funding across them.

The most aggressive attempt to ameliorate these disparities came in 1973, in a Supreme Court case, San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez. It began when a father named Demetrio Rodriguez, whose sons attended a dilapidated elementary school in a poor area of San Antonio, sued the state of Texas, claiming that the way that schools were funded fundamentally violated the U.S. Constitution’s equal-protection clause. Rodriguez wanted the justices to apply the same logic they had applied in Brown v. Board of Education—that every student is guaranteed an equal opportunity to education. The justices disagreed. In a 5–4 decision, they ruled that there is no right to equal funding in education under the Constitution.

With Rodriguez, the justices essentially left the funding of education a state issue, forgoing a chance for the federal government to step in to adjust things Since then, school-funding lawsuits have been filed in 45 out of 50 states, according to Rebell.

Though it might seem odd that the Supreme Court has ruled that Americans have a right to live in a better zip code and a right to work at a company no matter their race, but not that every American child has the right to an equal education, there is legal justification for this. The Founders didn’t include a right to an education in the country’s founding documents. Though the federal government is involved in many parts of daily life in America, schooling is, and has always been, the responsibility of the states.

The plaintiffs in the Connecticut lawsuit want the state to undertake an intense study of local schools and see what is needed to give each child a good education. They want the state to look at how much a district can reasonably raise from its property taxes, and then come up with a formula for how different districts can share revenues so that schooling is more equitable. They don’t just want poor districts to get more money; they want poor districts to get enough money so that disadvantaged children can do just as well as children from wealthier areas.

“We think the state’s responsibility is to ensure that every child, in every school, in every school district, regardless of whether they’re impoverished, is given the opportunity to graduate from high school, and be able to be a full citizen and active in the civic life of their town, state and nation,” Jim Finley, the principal consultant for CCJEF, told me.

If CCJEF wins, it might take a page from other states that have tried to radically overhaul how schools are funded from district to district. After the Vermont Supreme Court ruled that the state’s education funding system was unconstitutional, the state in 1997 passed Act 60, which ensured that towns spent the same amount of revenue per pupil. Districts paid into a common pool, which was then redistributed to poorer areas. And since the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled in 1990 that the state’s funding system was unconstitutional in the Abbott v. Burke case, New Jersey has been required to spend extra money in 31 of the state’s poorest school districts.

Asking the state to step in can also have its downsides. A court decision in California in 1971, Serrano v. Priest, found that the state system, which relied heavily on property tax, violated the state’s constitution because there was such great inequality. The state decided then to make sure spending in every district was the same, not allowing for any disparity. But then, when voters in the state passed Proposition 13 in 1978, limiting the amount of property tax homeowners pay in a given year, the state was left trying to equalize schools with a shrinking pot of money. The result has been extremely low levels of state funding available, and shrinking expenditures on public schools throughout the state.

The federal government has provided additional funding for poor districts since 1965, when Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), but federal intervention in schools has always been controversial, with many parents and school-district leaders resisting federal dictates about curriculum and standards. The 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, which reauthorized ESEA, received pushback after schools struggled to keep up with testing requirements and progress reports. That law was replaced in 2015 with the Every Student Succeeds Act, which rolled back the federal government’s role in local education.

In general, keeping schools equitable across a state is a tough task, says Odden, the school-finance expert. Immediately after a court case, there’s a lot of momentum for redistributing revenues. But then, as time goes on, the impetus for giving more to poor districts wanes.

There have been suggestions that it is time to change the school-finance system to one that more successfully directs resources to where they’re needed. Indeed, the United States is one of the only countries that allows the economies of local areas to determine the quality of local schools.

In 1972, a commission appointed by Richard Nixon came up with a far-reaching report, Schools, People, & Money. The Need for Educational Reform, about how over-reliance on property tax led to inequitable schools. It found that money was not being “collected equitably or spent according to the needs of children,” the commission reported. “We conclude it will be better spent when the bulk of it is raised and distributed by the States to their districts and schools,” it said.

It would have been a big change. But of course, states did not, by and large, change how they collected revenues or how their schools were paid for. It may seem logical that a state would step in and try to fund poorer districts; states don’t want to be known for low test scores and graduation rates, and will pay the price if their residents don’t get a good education. But giving money from rich districts to poor ones is politically difficult, as Connecticut has learned. And money is increasingly tight as states struggle with budget issues and have to spend more money on corrections, infrastructure, and Medicaid than they once did.

More than 40 years after the Nixon report, another big group, the Equity and Excellence Commission, again recommended that the nation change its school-finance system. New federal funding could be directed toward high-poverty areas, it said, and the country could decide what resources are needed to make sure every student gets a good education, regardless of what money is available.

“This is a declaration of an urgent national mission: to provide equity and excellence in education in American public schools once and for all,” Congressman Mike Honda wrote in the report’s foreword.

Rebell, who served on the committee, says the group came up with a remarkable consensus, but that the report was ignored by Congress. Any bills related to the report have gone nowhere. Instead, advocates of school equity are left to fight on the state level.

Opponents of school-finance reform often argue that money isn’t problem, and that increased spending won’t lead to better outcomes at schools in poor districts. But studies show that after courts order public schools to spend more on low-income students, students begin to do better and better in school. There may be challenges that go beyond what more equitable funding alone can solve, but it’s the best place to start.